Understanding Model Jet Engines

Design, Fuel & Lubrication

by John Salt - Last Update February 2026

When I first started doing research on model jet engines (also known as model turbine engines) years ago, I was at first amazed a jet turbine engine could be made so small and even though they were a few thousand dollars, I actually thought they would have cost more.

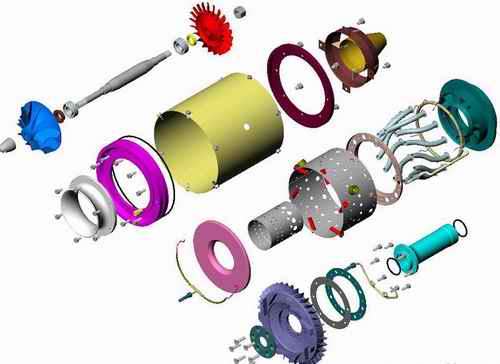

However, model turbine engines are actually very simple in design & principle; not at all like complex axial flow turbine engines.

After all, model turbine engines really only have one moving part - the main rotating shaft that is attached to the compressor wheel/blades at the front of the engine and the turbine wheel/blades at the back end.

Model Turbine Shaft Assembly - The Only Moving Part. Turbine On The Left, Compressor On The Right, Shaft Connecting Both.

Model Turbine Shaft Assembly - The Only Moving Part. Turbine On The Left, Compressor On The Right, Shaft Connecting Both. Diffuser Assembly

Diffuser AssemblyThe three most complicated parts of a model jet engine are the compressor, the diffuser/stator assembly, and the combustion chamber where the compressed air enters the combustor and fuel is vaporized and evenly distributed to ensure proper and complete combustion.

This is where model jet engine development costs are astronomical to even get these things to run; never mind run consistently & reliably throughout the entire RPM range of the model turbine engine.

Shown below is the stainless steel combustion chamber out of my Wren MW54 RC helicopter model jet engine while I had it apart for inspection and overhaul. The diffuser stator vanes shown aid in combustion and cooling as they redirect the swirling turbulent air from the compressor into a smooth flow, lowering the flow velocity while increasing pressure before being introduced into the combustion chamber.

Model Jet Engine Combustion Chamber

Model Jet Engine Combustion ChamberThe materials are very important and have to be of the highest quality to be able to withstand the high temperatures and the extremely high centrifugal forces produced.

The rear turbine in this model jet engine for example is cast from Inconel 713. The same expensive, exotic, nickle-chromium alloy that is used in many full size turbine engines.

Inconel 713 offers outstanding resistance to heat, oxidation, and thermal fatigue up to temperatures approaching 1000 degrees Celsius.

After all, the compressor and turbine blades are spinning upwards of 200,000 RPM.

I still can’t get my head around this number - that’s over 3000 rotations per second! Even at idle, these little engines are spinning at around 50,000 RPM (almost 1000 revolutions per second).

Exhaust gas temperatures can get as high as 850 degrees Celcuis during start up; the hottest and most dangerous time of all jet engine operation for model and full size alike.

As there is little airflow through the engine at this time, cooling is at it's lowest during startup. Hot start turbine damage (melted or over fatigued parts) is one of the most feared outcomes of improper starting of any turbine engine. Thankfully these days, the FADEC engine control system almost eliminates any possibility of hot start damage in our little model jet engines.

As you can imagine, machining tolerances are absolutely critical as is balancing on these little engines. It's the high quality materials, precision, hand assembly, and the decades long development costs you are paying for.

The two following photos show this precision & quality very well. During my Wren MW54H turbine engine overall where the ceramic bearing had to be replaced; I had to send the entire Inconel 713 turbine wheel and shaft back to Wren Power Systems Ltd. I could have replaced the bearing myself, but the turbine must be removed from the shaft to facilitate bearing access, and afterward the assembly would no longer be in balance.

Inconel Turbine Wheel Grind Locations For Dynamic Balancing - Note The Brand New Silicon Nitride Angular Contact Ceramic Bearing :-)

Inconel Turbine Wheel Grind Locations For Dynamic Balancing - Note The Brand New Silicon Nitride Angular Contact Ceramic Bearing :-) Shaft Grind Location For Dynamic Balancing

Shaft Grind Location For Dynamic BalancingAfter the technicians at Wren Power Systems replaced the bearing, they had to then dynamically balance the turbine and shaft assembly using a very precise dynamic computerized balancer.

Small amounts of metal are then ground off both the turbine wheel (both front & back faces) as well as on the front of shaft to achieve perfect dynamic balance of the entire assembly. This takes time, skill, and care to do correctly.

The video below shows a very "quick" overview of the model jet engine manufacturing process. Not everything is explained correctly, but you will get the general idea of "how it's made".

Here's another interesting video showing a see through model jet engine in operation.

Model Jet Engine Fuel

The fuel used in these little jet engines is the same as the big ones:

Jet-A, regular kerosene & some even allow use of readily available diesel. Follow your engine manufacturer's recommendations when in doubt and what you can source - more on that in a bit!

Now to model turbine engine lubrication, a polarizing and more hazardous topic!

Model Jet Engine Oil

Mobil 254 Jet Engine Oil

Mobil 254 Jet Engine OilYou must add a little bit of turbine lubrication oil such as Mobil 254, Mobil Jet II Oil, BP 2380, AeroShell 500, etc. to your Jet A, kerosene or diesel.

This oil is used to lubricate those little ceramic bearings on the turbine shaft that are spinning at warp speed and perhaps the second stage turbine bearing if you are running a two stage helicopter or turbo-prop engine.

Yep, oil choice is very important if you want your model jet engine to last.

Problem is, synthetic aviation jet oil contains some pretty nasty chemicals.

One of the most toxic among these is Tricresyl Phosphate (TCP); a chemical that causes peripheral neuropathy (nervous system damage). TCP is used in turbine oil as an anti-wear additive and while the concentrations are low at about 1-5% by weight in most aviation turbine oils, further diluted by your fuel to oil mix ratio, it's still very bad stuff.

Toxicity is of course dose and exposure dependent and it's not like we have our noses up the tail pipe the entire flight, but one has to consider long term effects; not to mention the fact it was never intended to be part of the combustion process in model jet engines.

Moreover, very little of the fuel oil mixture is actually diverted to the bearings for lubrication and cooling; so in effect, you are burning the vast majority of this toxic oil (along with your money) that isn't even being used for lubrication purposes.

Speaking of burning your money; Mobil Jet II, 254 and other aviation turbine oil is also getting bloody expensive and can be hard to find considering it's certainly not intended for the general public to be using. Up here in Canada we are shelling out about $40 for a quart (I get/got it from our local helicopter base which sells the stuff).

I'm not saying Mobil 254 or the others are not good model jet engine lubrication oils (I used 254 exclusively for a good number of years), but most model turbine engine manufacturers now agree it and other brands of aviation jet oil toxicity dangers largely outweigh their good high temperature, anti-oxidation bearing lubrication properties.

Some manufactures for example now recommend using a good quality 2-cycle oil; which after all has been designed to be burnt with limited toxicity. Keeping in mind, no atomized oil in a combustion process is safe to breath, 2-cycle or otherwise.

Problem with 2-cycle oil is some (certainly not all), can oxidize under the high heat, varnishing up the turbine bearing and/or gum up the bearing pre-load tube causing premature bearing failure. It can even gum up and block the fuel tubes in the combustor. In other words, only use a 2-cycle oil if your specific turbine manufacturer recommends it. If they do, use the exact brand/type they recommend.

Those that do authorize use of a 2-cycle oil, will generally recommend conventional based oil and not synthetic. Reason being is some synthetic 2-cycle oils don't mix well with Jet-A, kerosene or diesel and will settle out.

An easy way to test that is to mix some 2-stroke oil (or any lubricating oil) with your fuel of choice, put it in clear glass jar and let it sit on a window ledge for several weeks. If the oil doesn't separate from the fuel, you'll know for sure it won't settle out.

This is actually a good test for any new oil you decide to mix with your Jet-A, kerosene or diesel fuel to ensure the oil won't settle out.

Another popular & fairly safe recommended model jet engine lubricant by most small turbine manufactures is ISO 32 hydraulic oil such as Mobil DTE Light Circulating Oil (it's what I'm currently using).

The downside is it only comes in 5 gal/20L pails (at least here in Canada), but it's quite cost effective at about $40/gal ($10/L). Getting a pail with a another bloke to split the cost and quantity is what many do.

Mobil DTE 24 (also an ISO 32 grade hydraulic oil) can be used and it's generally easier to find, and in smaller 1gal / 4L jugs. I've used DTE 24 once when I couldn't get any DTE Light, and it seemed to work just as well as DTE Light.

I'M SO CONFUSED!

If you're scratching your head about what jet oil to use in your model turbine engine, you're certainly not alone.

Best recommendation is to check & confirm with your engine manufacturer and use what oil/s they recommend or perhaps what others at your flying club are using with good results if they run the same engine/s. Keeping in mind some model turbine engine manufacturers won't honor any warranty they may have unless you use their oil recommendations!

The main problem is there really is no lubricant that has been specifically formulated for model jet engines. For years now, the entire model turbine engine industry has basically been using whatever available oils seem to work the best with as few compromises as possible. This is changing however with the continued growth and popularity of these small model turbine engines.

KingTech for example has a dedicated model turbine jet engine oil using ISO 32 hydraulic/turbine oil as the base stock with proprietary additives specially formulated for use with these model jet engines.

JetCat also has their own formulation.

There is little science however, only anecdotal experiences and cherry picked, p-hacked data to support if these manufacturer supplied, proprietary formulated blends are vastly better than ISO 32 hydraulic fluid or aviation jet oil. You know, just like every other "this oil is better than that oil" debate, and I ain't about to go down that rabbit hole!

Regardless of what oil is used, typical fuel/oil mix ratios range from as low as 40:1 (about 2.5% oil) up to as much as 20:1 (about 5% oil) depending on the engine manufacturer and even what fuel type is used. Diesel for example already has some lubricating qualities and you may find lower oil mix ratio recommendations when using diesel over Jet-A. Regardless, always follow the engine manufacturer's mix ratio recommendations.

Last up on the model turbine oil topic is to never mix different oils because sometimes the synthetic jet oils may react to the non jet oils and gum up your entire fuel system or engine. If you do switch oils, it's always best to play it safe by flushing out your entire fuel system with fresh Jet-A, kerosene or diesel before introducing the new fuel/oil mixture.

Sources for Jet Fuel & Oil

Kerosene & diesel can be purchased almost anywhere (at least here in North America). Jet A fuel is available at most airports and heliports. You can purchase aviation jet oil from any aviation facility that services turbine engines/turbine aircraft. I've also seen it for sale on eBay and a couple specialty aircraft websites.

ISO 32 hydraulic oils can be found online at Amazon or eBay or at most commercial oil distribution centers. The special blended model turbine oils such as KingTech are available direct from the engine manufacturer and carried by some hobby shops that sell their engines.

Heliports seem to be more accommodating for Jet A fuel service since they are used to refueling in smaller amounts and have the proper equipment for it. I just take a couple 20L kerosene specific jerrycans (the blue ones) and a large funnel to our local heliport and they have no problems with pumping out small quantities like that.

It doesn't hurt to take your model the first time you befriend your local heliport or airport to explain exactly why you want a smaller quantity of Jet A (they will ask and want to know what it's being used for). Chances are they will be very interested in the model and want to know more about the hobby in general. It's a great opportunity to promote our hobby :)

With the basics out of the way - now let's find out how model jet engines actually work and function.